Don’t look now, but free-market economics is coming back into vogue.

For the last decade, mainstream economists of both the right and the left have begun to flirt with statist ideas that previously were beyond the mainstream: industrial policy, protectionism, massive deficits, anti-”bigness” antitrust, a rejuvenation of unions, and unprecedentedly high minimum wages. These policies look remarkably like the strategies adopted by developing-world populists and nationalists of the 20th century like the Peronists in Argentina, the Kemalists in Turkey, and the PRI regime in Mexico. But for whatever reason, these ideas — or some subset of them — became au courant, while free-market economics was seen as passé.

But the experience of the last four years, featuring the failures of deficit spending, industrial policy, and protectionism, has started to turn the zeitgeist around. Economists are returning to their bread-and-butter skepticism of the ability of central planners to outperform the market.

For evidence of this, look no further than economics blogger Noah Smith. Smith’s mainstream credentials are impeccable — he studied at the University of Michigan, taught at Stony Brook, and then wrote for Bloomberg before setting up his own Substack: Noahpinion.

Smith exemplified the discipline’s turn toward embracing policy prescriptions once viewed as heterodox. While never an advocate of across-the-board protectionism or fruity ideas like modern monetary theory, Smith did endorse industrial policy and deprecated “libertarian” concerns about government intervention. He was always an interesting and provocative commentator, and I enjoyed reading his challenges to my thinking.

I long associated him with the atheoretical turn in economics that happened around 15 years ago: just run the regressions, with proper causal identification, of course, and the results give you truth. It doesn’t matter if you can’t find monopsony power in unskilled labor markets, speculation seems to go, the minimum wage doesn’t reduce employment. We don’t know why, but if the data say so, it must be true. The effects of a price control in industry X tell you nothing about the effects of a price control in industry Y.

The anti-theory turn in economics seems to have run its course since then. The replication crisis in the social sciences showed us just how much even methods with strong causal identification, like experiments, can be manipulated. Instead of taking each empirical finding at face value, we need to read whole literatures that show how different empirical findings fit within a theoretically coherent whole.

Even the empirical minimum wage research has come back around to standard theoretical predictions, with a twist. It seems that employers respond to “small” minimum wage increases by raising prices and reducing job perks, benefits, and scheduling flexibility and consistency, while waiting for inflation to erode the hike. But they respond to “large” and inflation-indexed minimum wage increases by shedding hours and even headcount, in addition to the listed strategies.

Smith has paid attention to these shifts in the discipline. A self-described “liberal” in the modern, left-of-center sense, Smith isn’t naturally sympathetic to free-market economics. In the 2010s, he dedicated a lot of time to criticizing libertarianism, largely for ignoring, in his view, the need for government provision of public goods.

But since 2023, his tone has changed. It started with a post in June of that year in which he noted how libertarian critiques of regulation were starting to bear fruit again, citing the problems of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), restrictive zoning regulations, Europe’s tech regulations, and policies that did not work during the pandemic, like the FDA’s slow-walking of drug approvals. Moreover, he saw the disappearance of libertarian ideas from policy discussions as a real loss of a counterweight against annoying, paternalistic regulations: “I also think libertarianism should retain some of its zeal for battling regulations that impose undue burdens on our daily lives, even if those burdens ultimately don’t affect economic growth. Pointless plastic straw bans and rules that make children use car seats through the age of seven aren’t going to change our descendants’ standard of living a thousand years from now, but in the present these little things can add up to a very annoying blanket of social control.”

Smith’s change of heart continued this year. In April, in a post titled, “I Owe the Libertarians an Apology,” Smith argued that the weakness of libertarian ideas in the national Republican Party has allowed the Trump Administration to pursue a destructive protectionist agenda without any internal checks. It would have been far better, Smith says, if libertarians had maintained a leading role in the Republican Party. (Yes, he thinks libertarians once had a leading role in the Republican Party!)

But Smith also recognizes the failures of progressives in the Biden Administration. In particular, Biden’s industrial policy agenda worked far more poorly than Smith had anticipated at the time, with the federal government struggling “to build high-speed rail, EV chargers, and rural broadband, despite throwing tens of billions of dollars at these things.” And he recognizes that many left-wing wonks seem to support government regulatory barriers as an end in themselves, despite the harm they do to progressive objectives like decarbonization.

Journalists Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson have made a similar discovery. Although not trained as economists, they have found that government red tape often ties down entrepreneurs and builders in ways that hurt progressive goals. In their bestselling book Abundance, Klein and Thompson offer a policy agenda they call “supply-side progressivism.” Their left-wing critics call it “neoliberalism repackaged,” and the left is probably right to see it that way. It’s been over a decade since libertarian-ish political theorist John Tomasi explored how a free-market agenda could achieve progressive goals much better than social democracy, but if rebranding these ideas makes them more acceptable to voters and politicians, so much the better.

Just last month Smith wrote a post titled, “Free-Market Economics Is Working Surprisingly Well,” pointing out that libertarian Javier Milei’s Argentina has performed far better than left-wing economists predicted.

Smith really shouldn’t have been surprised. The evidence in favor of free-market economics is overwhelming. The more free-market a country is, the faster its economic growth. At the U.S. state level, the more free-market a state is, the more people it attracts from other states and the faster its personal income grows. We don’t know the limit at which it is possible for an economy to have too much freedom, but what we do know is that no polity on earth has reached that limit in recent decades.

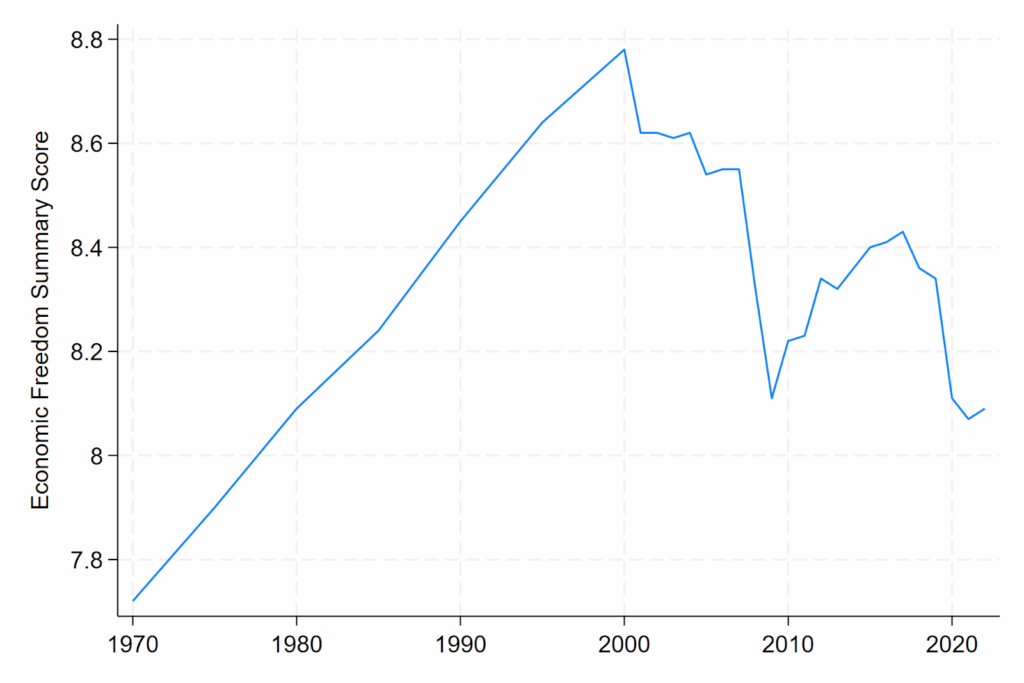

Smith still doesn’t understand libertarianism very well. That is evident from his repeated invocations of the George W. Bush Administration as a test of free-market policy. Yes, the same Bush Administration that exploded federal deficit spending, added a new entitlement program, nationalized airport security, raised the minimum wage, and signed into law one of the most costly regulatory expansions of this century in the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. The reality is that the era of neoliberal reform in the US lasted only from about 1975 to about 2000, and we’ve been in a period of statist retrenchment ever since. Economic freedom scores support this timeline (Figure 1).

Economists’ changing attitudes toward free-market policies are welcome. Time will tell if this is just a two-year blip or the beginning of a trend. Smith is right: the world needs a hefty dose of free-market libertarianism right now, if we’re to avoid an economic Dark Age of protectionism, dirigisme, and stagnation.