Imagine a friend of yours who is $456,000 in credit card debt said to you, “I’ve got a plan to make an extra $3,010 per year and get myself back on track.” You know this person well enough to know that their salary cannot be much more than $62,000. Would you roll your eyes at this person’s claims or would you listen intently and think, “By golly, this person is on the right track!”

Unfortunately, this situation is exactly what the White House is peddling to the American people right now.

Just last week, the Congressional Budget Office sent a letter to Democrats who had requested an estimate of the revenue generation of the tariffs. Put simply, the CBO projects that the Trump tariffs enacted between these dates would lead to an overall reduction in the federal deficit of $2.8 trillion over the next decade.

The Administration and most of the media are touting this as a massive victory for fiscal health. Some are even pointing to it as evidence that “Trump was right” and social media is replete with virtual high-fives and congratulations. However, in doing so, these pundits are committing a fundamental mistake: conflating deficit reduction with debt reduction.

Deficits vs Debt: A Clear Distinction

The distinction between deficits and debt may seem trivial, as many use the two interchangeably. This conflation might not mean much in our everyday, personal lives, but the distinction makes all the difference when it comes to federal budgets. To put it simply, a deficit occurs when there is annual overspending. For example, suppose your friend earns $62,000 per year, which just so happens to be the annualized earnings of the median full-time wage and salary worker in the United States, according to the BLS. If they spent $85,000 per year (37 percent more than their income), they would be engaged in $23,000 per year in deficit spending. This would have to be financed by borrowing money from friends, family members, banks, or by opening a new credit card.

Debt, by comparison, is the total accumulation of all the deficits (and surpluses) incurred over multiple years. If your friend’s financial situation remained unchanged for an entire decade, then we would say that they ran deficits of $23,000 each year and that this resulted in a total debt of $230,000.

So what does this have to do with the White House and what they are telling the American people? In a word: everything.

If we look at last year’s figures, the federal government had total revenues of $4.92 trillion against $6.75 trillion in spending. This difference is the source of the $1.83 trillion in deficit spending for just 2024 alone. Incidentally, this is 37 percent more than they took in in revenues for 2024. By comparison, it took until 1981 for the total federal debt to hit $1 trillion. In fact, President Reagan warned about the coming “incomprehensible” trillion-dollar national debt during his first address to a joint session of Congress in February of 1981. The federal government increased the national debt by just under $2 trillion in just 2024 alone. Just like a household, this deficit spending must be financed somehow. The government can borrow the money by issuing debt, akin to borrowing money from friends, family members, or a bank. Unlike a household, though, they have another route: inflating the debt away by printing more money.

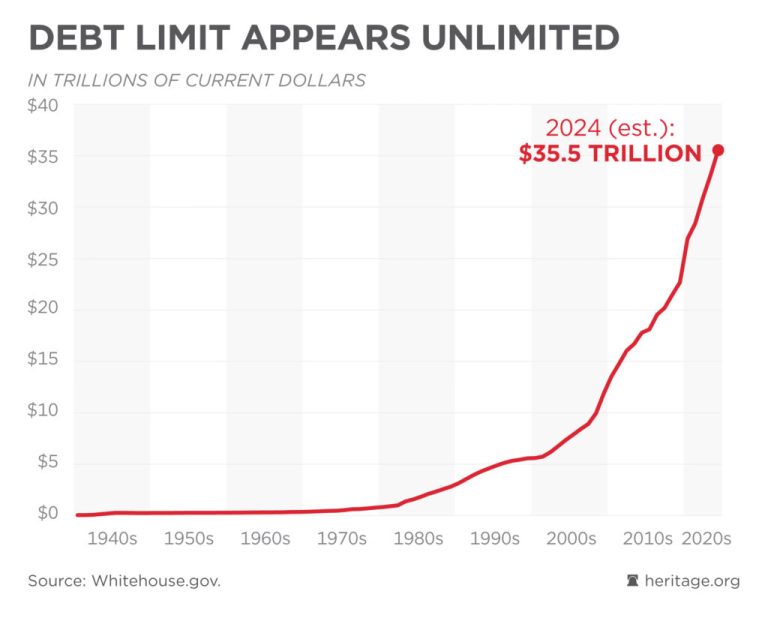

If we add all the previous years’ deficits (and surpluses) for the federal government, we arrive at their current level of national debt: a staggering $36.2 trillion. This gives the federal government a debt-to-income ratio of 7.4. In other words, to pay off the national debt, the federal government would have to allocate every single penny of the budget for the next 7 years and five months, assuming zero interest on the debt. If your friend ran his budget the way Congress runs theirs, he would have $456,000 in credit card debt.

The CBO’s Letter

So what about that letter the CBO sent? It announced that the tariffs, assuming that they are reinstated, last all ten years (i.e. are not rescinded by a future administration), and are not evaded at all (these are Herculean assumptions), then the total deficit over the next ten years will be reduced by $2.8 trillion. That works out to an average of $280 billion per year. But what effect will this have on the total deficit each year? The CBO projects that the deficit for 2025 will be $1.9 trillion.

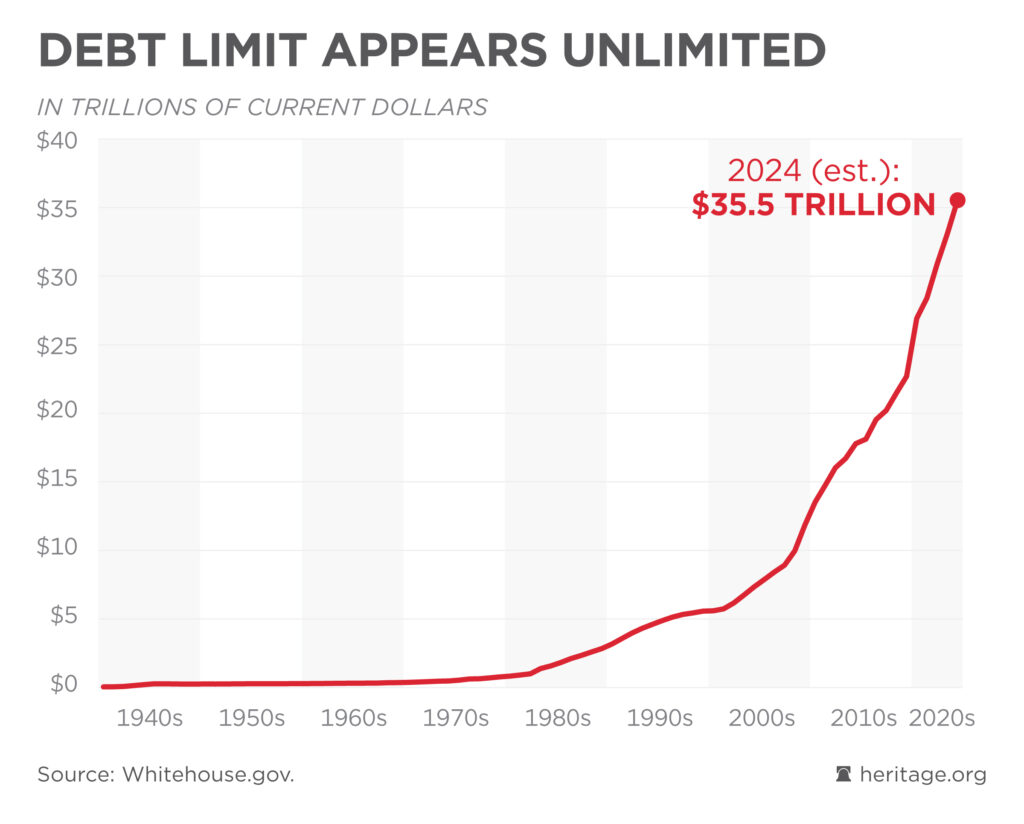

Cutting $280 billion from this would reduce the deficit to $1.62 trillion. Going further, the CBO projects deficits for each of the next ten years as well. And while there are reasons to believe that these numbers will not prove to be accurate in the future, they were determined the same way as these savings. Over the next ten years, the CBO projects that we will run deficits totaling $21.8 trillion. The additional tariff revenue will reduce this to $19 trillion.

Extending this to the national debt picture, the CBO’s letter says that the national debt will not grow to $58 trillion in 2036 as they had originally predicted, but instead a “mere” $55.2 trillion.

Returning to the analogy of our friend, this would be akin to him only going another $201,000 in debt over the next ten years instead of an additional $231,000, growing his overall debt to $657,000 instead of $687,000.

This individual component of the President’s fiscal plan is a step in the right direction, sure, but there is absolutely no reason to throw a parade over this. Even in isolation, this will still result in a growing level of federal debt. We can see this plainly when we consider the CBO’s score of, for example, the Big Beautiful Bill, which finds significant overall addition to the national debt, over and above the savings from the purported tariff revenues.

Eating The Elephant

Reducing the federal deficit by $2.8 trillion over the next decade sounds impressive to us mere fiscal mortals. But it is at best a drop in the bucket when the national debt is, even under charitable assumptions, projected to grow to $55.2 trillion over the next ten years. Retired Admiral Michael Mullen, then the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, warned of our national debt’s effect of crippling our nation’s capabilities, making us less safe. His warning came in 2010, when the federal debt was a mere $13.5 trillion and the federal deficit was a mere $1.29 trillion.

While it is true that the best way to eat an elephant is “one bite at a time” and we certainly should celebrate taking this bite out of the problem of national deficits, the need to have a frank and serious conversation about our nation’s current fiscal reality has never been more urgent. Indeed, there is still much more of the elephant to eat and unfortunately, the task before us is only getting larger, not smaller.

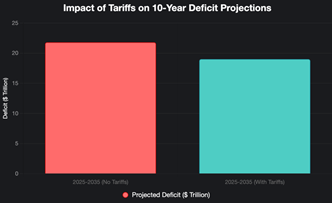

Solving the national debt through increased revenues is, quite simply, not going to happen. We have let it grow so large already that the level of taxation necessary to do so would absolutely devastate our economy and result in the impoverishment of virtually every American. This needs to be tackled through spending cuts.

But “excess spending” is a symptom of the true problem, not the cause. The real problem is that we have assigned far too many responsibilities to the federal government, several of which they have no business having in the first place. The increased delegation of responsibilities has led inexorably to the growth in the federal budget over time.

We cannot afford to celebrate half-measures like tariff revenues. Without deep, structural spending cuts and a fundamental rethinking of what government should do, we will only kick the can further down the road and burden future generations with even more crippling debt that will crush the American dream. Time is running out for the serious conversations that need to happen.