As the nineteenth century turned into the twentieth, the French were looking for a buyer for their failed Panama Canal project, asking for $109 million, well less than half their cost. The United States, toying with the possibility of constructing a canal through Nicaragua, offered a paltry $40 million, which the French accepted.

Legally, there remained the matter of obtaining permission from the host country. We solved that little problem with cash payments to the new and the former host countries.

Health-wise, there was the problem of overcoming tropical disease and, engineering-wise, there were the problems of constructing a canal through marsh lands and mountains, in the face of incessant landslides, along with the problem of supplying water sufficient to operate the locks of the canal.

The United States tackled the problem of tropical disease head-on. Finally connecting malaria and yellow fever to mosquitoes, the United States drained the swamps, introduced netting and window screens, and made other public health improvements, and practically eliminated those diseases in the vicinity of the canal. Even so, some 5,000 workers succumbed to tropical diseases and other workplace hazards in the construction of the Panama Canal.

The problem of water was solved by damming the Chagres River to form Lake Gatun. The lake became part of the canal route, and a reservoir for the water needed to operate the locks of the canal. The dam also regulated the flow of water, reducing the problem of landslides.

The monumental effort of excavating dirt and otherwise molding the path of the canal, and of constructing locks and other infrastructure, was largely directed by George Washington Goethals. Goethals was a West Point-trained officer and a civil engineer. He came to the project as a Lieutenant Colonel and eventually rose to the rank of Brigadier General. Goethals was appointed chief engineer in 1907 and remained in charge until the opening of the canal in 1914, two years ahead of schedule. He subsequently served as the first Governor General of the Panama Canal Zone and as Quartermaster General of the Army.

The project was started under President Theodore Roosevelt, continued through the administration of William Howard Taft, and was completed while Woodrow Wilson was in office. On October 10, 1913, President Wilson sent a signal by telegraph from the White House to the Panama Canal that triggered the explosion of a temporary dam, opening the canal for traffic.

Operating the Panama Canal

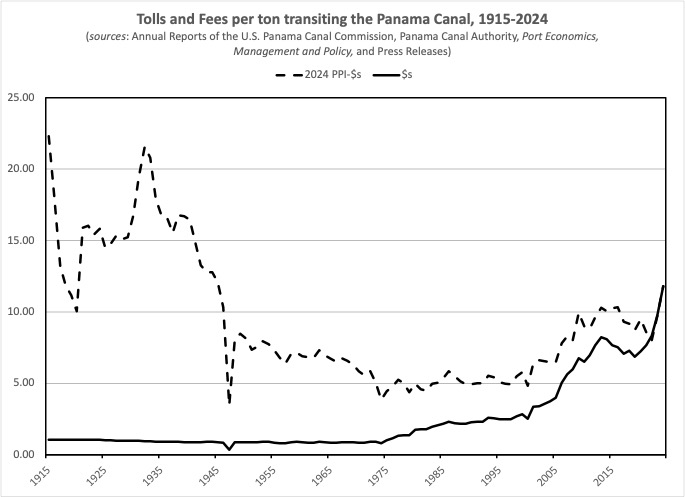

From its opening to when we turned the canal over to Panama, we ran the Panama Canal on a break-even basis. After gaining control over the canal, Panama jacked up tolls several times and also instituted fees. Essentially, Panama has acted like a monopolist, charging what the market will bear. Considering that Panama got the canal at no cost, net income and fees have been pure profit to the country.

In addition to higher cost, passage through the canal has come to involve waiting times. The higher cost of passage and waiting times have caused shippers – who mostly serve Americans – to consider their options.

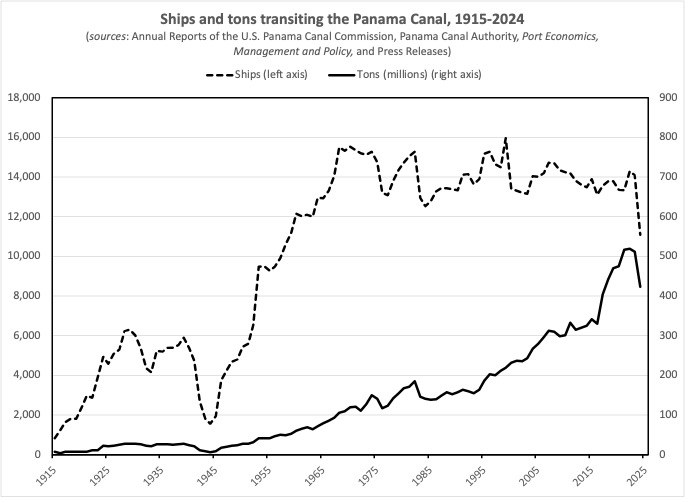

As the following chart shows, the United States built up traffic during the first several decades of the Panama Canal. The dip in the number of ships passing through the canal during the 1940s was due to World War II.

By the 1960s, the number of ships passing through the canal reached 14,000 per year, at which level it has since fluctuated (see the dashed line in the chart). Because of the increasing size of ocean-going freighters, tonnage passing through the canal has continued to rise, even dramatically, although the number of ships has leveled-off (see the solid line in the chart). In recent years, huge container-ships and specialized bulk-cargo ships have come to dominate ocean-going freight.

Notice the fall in ships and tonnage in 2024. The canal may have effectively reached its limit.

The next chart shows tolls per ton; or, tolls plus fees per ton once fees were instituted. For the first several decades, we basically charged a toll of $1 per ton (see the solid line in the chart). During the inflationary 1970s, we started increasing the toll; but, the increases essentially adjusted the toll for inflation (see the dashed line in the chart). After the canal was turned over to Panama (2000), tolls plus fees have approximately doubled, from $5 per ton in today’s money to $10 per ton.

Getting back to the period of US operation, our motivation involved both raising revenue and serving the shipping community (and, ultimately, the producers and the consumers of the goods passing through the canal). Then, as now, the vast majority of ships transiting the canal originated on and/or were destined for US ports. Our balancing of these concerns underlaid our break-even pricing.

Panama’s motivation is very different. To Panama, all the ships passing through the canal originate and are destined for other countries. Their only interest is in maximizing profit. Besides, with the canal at or near capacity, charging what the market will bear might be the most efficient way to allocate passage.

How to Break Panama’s Monopoly

Since the nineteenth century, world trade has been propelled by advances in transportation as well as by trade agreements (ignoring times of retrogression). Trade has grown faster than world GDP and the infrastructure of trade has not kept up. The Panama Canal is now at or near capacity, but so are many other components of the global transportation network. The Panama Canal has been jacking up its price for transit, acting like a monopolist. It is understandable that shippers are balking at increased prices, but one of the purposes of price is to allocate scarce goods and services among competing buyers. Another purpose of price is to induce additional supply.

This, the final installment on the Panama Canal examines what alternatives there might be for interoceanic freight.

At least in theory one alternative to the Panama Canal is to sail around South America. And, perhaps another is to sail around North America depending on the prevalence of sea ice in the Arctic. A major problem with these options is financing the cargo during the longer voyage. In business, time is money and is quantified by the interest rate.

A more practical alternative might be to unload at an American port and complete the shipment using rail or pipeline. The problem with this idea, as already mentioned, is that many American ports are, like the Panama Canal, effectively at capacity. Eureka, California, north of San Francisco, has enormous potential as a west coast port, but lacks good connections with the country’s rail network.

The possibility of a canal across Nicaragua has been explored from time to time, most recently by a Hong Kong-based company. We, ourselves, were interested in such a canal prior to our commitment to the Panama Canal. The investment needed for a canal in Nicaragua seems very risky given the increasingly autocratic government of that country.

Mexico has recently rehabilitated a railroad in the southern region of the country described as the Interoceanic Corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, as well as has improved freight handling facilities at its two ends. A railroad there was completed in 1907 and was successful until the opening of the Panama Canal. Its business then collapsed and the railroad fell into disrepair.

In the late nineteenth century, it was argued that the shortest route from the American midwest to the Pacific was through Topolobampo, Mexico, on the Bay of California. A company was formed to develop this route, the Kansas City, Mexico & Orient RR. Crossing the Sierra Madre in the vicinity of Topolobampo proved too difficult. The road was never completed and eventually was broken up and sold. Perhaps today, the Canada Pacific Kansas City RR can revisit this idea.

While there are potential alternatives to the Panama Canal, these alternatives typically require enormous investment and involve tremendous risk. It is one thing to complain about high prices. It’s another thing to actually do something about it.